Returning to Sport Post-Abdominal Surgery Series: Understanding Anatomy to Build a Stronger Athlete3/21/2021  Rainey looking real cute! Rainey looking real cute!

Today marks day 69 post-abdominal surgery for Rainey, and tomorrow is the start of week 10. Last week Rainey did agility Thursday and Sunday. We did not exercise those days, or on either of the Mondays at the start and end of the week. This allowed for a recovery period, which is important for muscle healing and regeneration, even in dogs. They can do normal dog things, like go for a walk or play with house mates, but doing exercise day after day after day is just too much for them. Unlike humans, a dog won’t stop. It is up to the human to stop the dog. A dog does not know what is in their best interest. Ask every dog who ever went face deep into a porcupine. They didn’t know better, therefore ended up with a face full of quills.

Rainey did not demonstrate any extra soreness or tiredness from her extra days of agility. The seminar we attended contained a lot of running, which she hasn’t done in a while. She was tired Sunday evening, but by Monday she was energized again. This coming weekend we are running in a UKI agility trial. I will take each run and each day as they come, assessing what will be best for her. If she appears to be enthusiastic by end of day, we will keep running. If she is tired and over-aroused like a child who needs a nap, we won’t run. Simple as that.

This week’s topic is going to focus on anatomy. Earlier this week I saw a social media post of a dog backing up stairs. It was a larger breed dog and it was only 2 stairs, so not that bad. What was bad was the dogs head position. Its head was cranked up over his shoulders, as the reward placement was at a height that was convenient for the handler, not what was best for the dog. At the same time, the dog was being asked to lift its hind end at an angle while backing up stairs. However, from its head placement, it was shifting the majority of its weight to its hind end, which makes it much more difficult to appropriately lift the hind legs. Not to mention the stress this head placement was putting on the dogs cervical-thoracic junction. The handler was receiving all sorts of likes and comments on how wonderful this was. I had to move on. It was hard for me to watch that video without wanting to comment that this was actually harmful for the dog, for several reasons. Backing up is a difficult task. Backing up stairs is an extremely difficult task. Backing up stairs with your head held high is nearly impossible and will create pain at the transition zones of the spine if continued frequently.

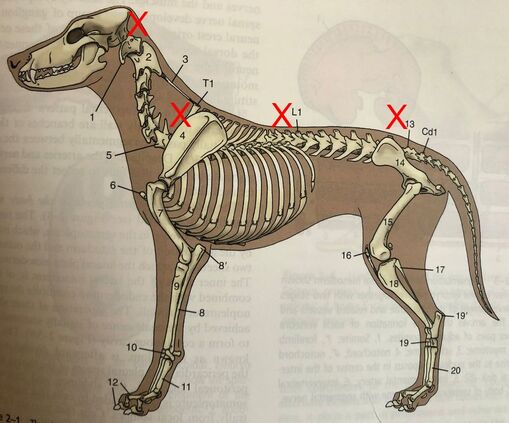

But what are transition zones of the spine? These are areas where one type of vertebrae is changing to fit to the next type. The sections include: occiput to cervical, cervical to thoracic, thoracic to lumbar, and lumbar to sacral. In dogs there are 7 cervical vertebrae, 13 thoracic, 7 lumbar, 3 sacral (which are fused to form the sacrum), and 20 caudal or coccygeal vertebrae, depending on breed and tail docking.

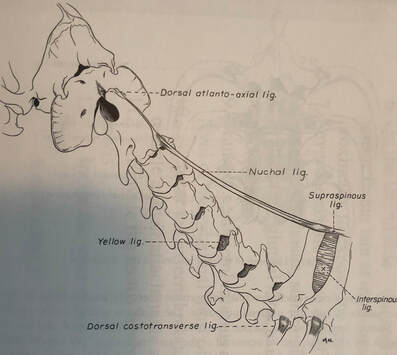

The occiput to cervical region is at the base of the skull, and isn’t commonly thought of as a transition zone, as its not a location where a disc can be herniated. There are actually no intervertebral discs at C1, C2, or the coccygeal vertebrae. An intervertebral disc is a fibrocartilaginous structure consisting of a soft center (nucleus pulposus) and surrounded by concentric layers of dense fibrous tissue (anulus fibrosus). They are the shock absorber during physical activity. The intervertebral disc is what we think of when we say ‘the dog herniated a disc’ aka the disc is protruding from its location between vertebral bodies and putting pressure on the spinal cord, resulting in inflammation and pain. The disc space is what we look at on radiographs when assessing for back health, aside from spondylosis and other arthritic indicators. When a disc becomes unhealthy or a traumatic injury occurs, the disc space narrows as the disc protrudes out of the space and into the spinal canal, resulting in inflammation, pain, and possibly neurological dysfunction.

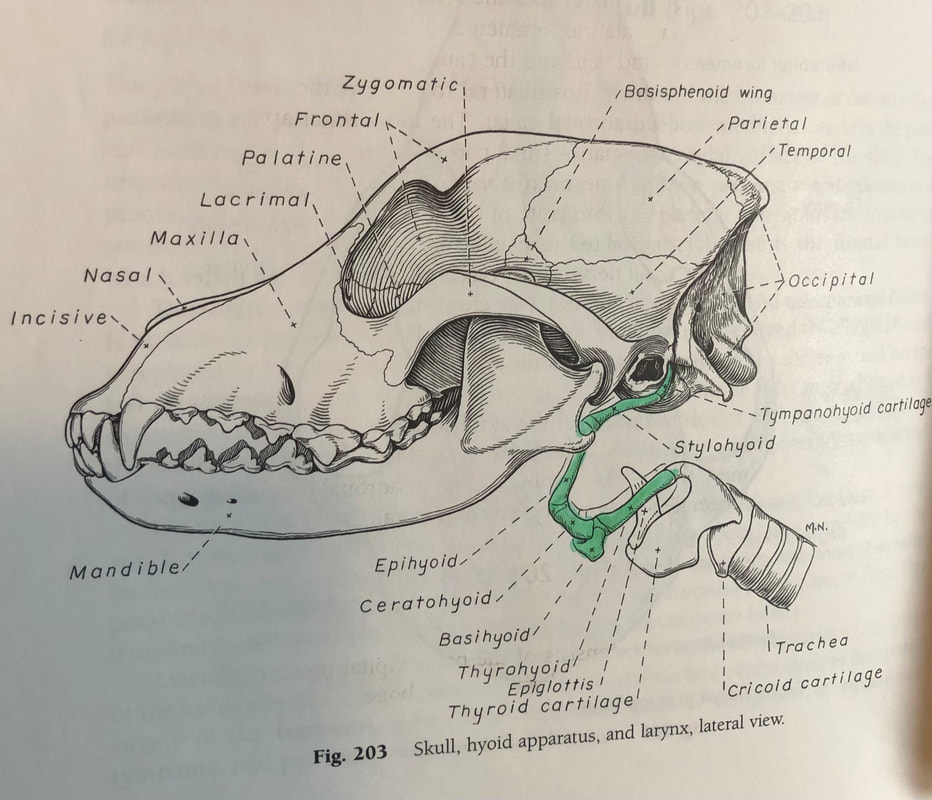

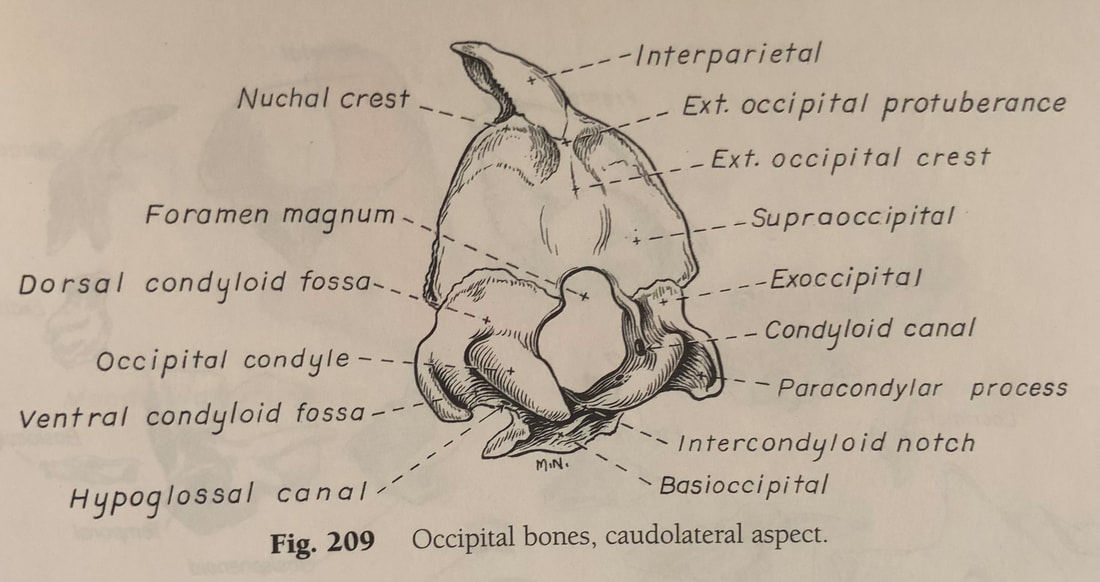

The Occipital, C1, and C2 region is the location that can become very stiff when a dog is always heeling on one side of a handler (ie always looking up with their head turned to the side). The occipital protuberance is the large bulge on the back of the head. Most prominent in breeds such as setters. The occipital condyle is at the lower portion of the occiput, and it articulates with the atlas to form the atlanto-occipital joint. The main movement of this joint is flexion and extension. The wings of the atlas are the bulges on the side of the neck closest to the head that you can feel. Cervical vertebrae 1 (C1) is the atlas. C2 is the axis. The atlanto-axial joint is responsible for rotary (left and right) motion of the head. There is a lot more going on here, but we will keep it simple. The axis, as seen in the photo with just the cervical spine, has an elongated ridgelike dorsal spinous process and has characteristics different than other vertebrae.

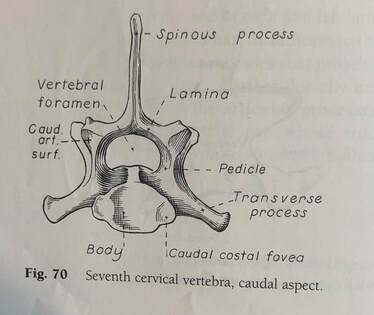

As we move down the spine, and visible on the photo of the cervical spine is the cervical thoracic junction. There is a lot to be said about the thoracic vertebrae. Mostly, each thoracic vertebra has a corresponding rib and as you move down the thoracic vertebra the shape of the bones change as they transition to the lumbar spine. At the C7-T1 junction, you will note that C7 has the highest dorsal spinous process (the bone pointing upward) of all the cervical vertebrae. This is so it starts to match the upcoming thoracic vertebrae. However, they are not perfect fits. This brings forth the issue with the transition zones. Note – not to be confused with transitional vertebrae, which are congenital anomalies of deformed vertebrae. Transition zones are weak by nature. You cannot expect two opposing bones to fit perfectly, but the body tries very hard to make the perfect match. Because they are not perfect and they are changing from one type to another they are weak areas in the back. The 3 remaining zones (cervical thoracic, thoracolumbar, and lumbosacral) are the points in the back to most commonly suffer injury. This is due to what has previously been mentioned, and the simple fact that they are weak zones. That is just nature. Yes, a disc can herniate at another location, but these are the 3 most common locations.

Back to the cervical thoracic junction. Not only is this region at risk for herniation, it is extremely protected and therefore extremely difficult to properly assess. What puts this region at risk of injury? The previously mentioned backing up the stairs with head held high or any activity that puts the neck in a high, hyperflexed position, especially if a concussive action (landing) is to follow. In the simplest of ways to think about this, think of holding a grape between the left pointer finger and the right pointer finger. There are a few positions that you can do that keep the grape (disc) stable and happy. But if you look at the adjacent photo of C7 from behind (caudal, so looking tail to head through the spinal canal), then the lateral (side) view of the cervical and T2 photo with scapula removed, and then the side photo of the dog skeleton, you will see how sharp the angle is from C7 (marked with a 5 in the full dog photo) to T1. Remember, the spinal cord is ABOVE the disc space. Now, use your imagination and picture what is actually happening to the joint space and disc space of C7-T1 when you ask a dog to hike its head up while its rear is going up. It’s not pretty and it sounds pretty painful, even without a disc herniation. And now you can imagine how a disc herniation could happen at this location. This is why I stress A NEUTRAL NECK!!! A neutral neck is a neck that is in alignment with the spine while you are performing an activity. When the dog is performing front feet on floor and back feet on a thing their head position is an elongation of their back. It is NOT hiked up creating a sharp angle from neck to thorax. Now you understand why. Physics, my friends, physics. Oh, and anatomy. Think of how dogs move and how their bones move. It will help you create a better exercise program for them and prevent injuries. An injury to the C7-T1 junction is subtle. Like I mentioned, this area is deeply hidden under lots of muscle and the scapula. Due to the brachial plexus being in this region, a sign of a C7-T1 injury may be front limb lameness. It may also be reluctance to lift their head. Or it could be spasms when that region is palpated. If this disc space ever has to be surgically relieved, I have heard it is extremely difficult to access. I can only imagine.

As we move down the thoracic vertebral column, you will notice that the dorsal spinous processes decrease in height slightly, but remain pointing towards the tail (caudal), giving you the sloping appearance from shoulder to back. Once you reach T7 or 8, the spines become progressively shorter, and when at T9 or 10 they are at their shortest point. At T11, the dorsal spinous process is nearly pointing straight up. In a lean fit dog, you will notice a dip in their back at this point. This is called the anticlinal region. T12 and T13 continue to change direction of their dorsal spinous process, pointing toward the head (cranial).

As we enter the lumbar vertebrae, they dorsal spinous process continue to point forward and the bodies of the lumbar vertebrae are longer than that of the thoracic vertebrae. The lumbar vertebrae also have transverse processes projecting of their sides and pointing toward the head. L1 has minimal transverse processes, and as the lumbar vertebrae go on, the transverse process gets larger. The transverse processes serve as attachment sites for the epaxial muscles of the back. The articulation (joints) of the last portion of the thoracic and lumbar vertebrae allows for flexion and extension of this section, but limits lateral motion. This brings us to the thoracolumbar junction, which is one of the most common regions for disc herniation. Based on the previously mentioned anatomy, you can imagine that this area is not as strong at other regions of the thoracic or lumbar spine simply due to all the boney changes in this region. If you look at your dog, you will also note that in this region there are fewer muscles. The C7-T1 region is well protected with muscle. But the T13-L1 region does not have that degree of stabilization. Therefore, if your dog is being asked to be extreme tasks, such as tight turns for a region of the spine not necessarily meant to bend laterally, abrupt landing where there may be extreme flexion at the T-L junction, or even a small dog being picked up by their mid-section, this area will become broken down much faster if it does not have the support of a strong core and strong back musculature. Again, think physics with anatomy.  Rainey demonstrating proper form with a neutral neck & straight back. Rainey demonstrating proper form with a neutral neck & straight back.

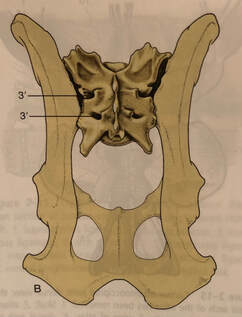

As we move down the back, we come to the lumbosacral region. It is important to note that at L6-7 the spinal cord comes to an end, therefore leaving unprotected nerves in the canal. Since there are still discs between the vertebral bones of L6-sacrum, this means when a disc herniates in this region it is applying pressure directly to nerves, not the nerves protected by the spinal cord. This is why dysfunctions in this region are extremely painful. The sacrum, as previously mentioned, is 3 bones fused together, and the bones is located between the ilium of the pelvis, which it articulates with. The disc space between L7 and the sacrum is the largest space and the highest motion joint space of the spine. As such, this location is predisposed to injury. This is the location, along with the T-L junction, that is most at risk when a dog goes butt over head (think an uncontrolled A frame, or even a stopped A frame).

This has been a fairly brief overview of the 3 major transition zones of the spinal column. I hope it has provided you with useful information on why we do the things we do – why form is so important with exercises, and how building muscle appropriately can help keep these zones intact, aiding in a long, healthy career for your dog. I realize this topic should have been covered sooner in this blog series, as it would have provided better understanding when I described Rainey’s exercises. But, from reading this I hope you can understand the difficulty in organizing this information. I’ll admit, I was dreading it. There is so much more that can be described on these 3 transition zones – muscles attachments, articular facets and rotation, exercises to stabilize and strengthen, etc. But my hope is you will look through the videos of Rainey’s exercises and see that I have already taught you the importance of proper form and function. Now you understand the WHY!!! Days 63 to 69 – Continuing to Build Strength This weeks exercise schedule. This weeks exercise schedule.

Squats – this an a very difficult exercise that strengthens the gluteal muscles and hip flexors, as well as the large muscle groups of the hind end. I used the Cloud as a way to ‘roll’ Rainey into a sit, while keeping her front legs elevated. Then she slowly and controlled, pushes herself upwards to a stand, with all feet remaining stationary. Like I said, this is very difficult, but also very rewarding, as it is great for strengthening.

Rocking Sit to Stand with Elevation – the purpose of changing up the Rocking Sit to Stand is to work her muscles a little differently. It does take away the power component, and maybe once she’s more practiced at this form she will regain a power drive from the rear. This attempt was her first and she’s still trying to figure it out. A couple critiques – try to maintain a straight back in the stand position. We weren’t the best, but tried for it. Second – to lure her into a sit I did have to have her head/neck a little too extended for my liking, noted especially after watching the video. Therefore, a better start for this would have been have dog sit on the balance pad and stand to the FitBone. This goes to show that videoing is very helpful. Plyometric Jump Progress – everything seems to be paying off, as Rainey is now able to make the jump about 3 or 4 times her height from a sit! She isn’t clawing her way up the Peanut, instead she is powering from her rear and landing on the top of it. She looks good! The set up is 1 KLIMB with the tiny legs, 1 KLIMB with no legs, and an upside down KLIMB. Wobble Board/FitBone/KLIMB – I wanted to share an updated version of this exercise, paying more attention her form. Note in this video the lure is held lower, which is making the position of her front legs and elbows less stressed. I try to maintain a neutral neck. I am also moving the wobble board in various directions for her to keep the stimulus novel. She does a great job stabilizing and maintaining her form. Diagonal Leg Lift Core & Strength Assessment – Rainey continues to have a strong core and excellent core engagement! If I were not adding this to blog videos, I likely would only assess this once every few weeks or once a month. Despite having this done weekly, Rainey still does not appreciate it. From her side profile, Rainey still looks great! There is not much new to report. Hopefully before the week 12 post she will get groomed, which will aid in demonstrating her fitness.

I continue to be very happy and proud of Rainey’s improvement and progress! She continues to get better every week! This is week 10 of Rainey’s recovery process. That means I have 2 more weeks of blogs left. Next week we will return to an agility trial, and I am not sure I will have time to write a large post. It will possibly just be a summary of her trial experience back from recovery and COVID. She has not participated in a trial since October 2020. In the remaining two posts, I will discuss warm-ups and cool-downs, along with Tui-na massage, which is a large part of my dog’s warm-up program.

The road to recovery is long, and sometimes there are setbacks, but the time it takes to get there will always be worth it! Take care and may the Qi flow freely for you! Dr. Shantel Julius, DVM, CCRP, CVA, fCoAC, CVSMT, CVFT, CVTP, CVCH, CTCVMP References: Millis, D., Levine, D. Canine Rehabilitation and Physical Therapy, 2nd Edition. Elsevier. 2014. Evans, H.E., deLahunta, A. Guide to the Dissection of the Dog, 6th Edition. Saunders. 2004. Dyce, K.M., Sack, W.O., Wensing, C.J.G. Textbook of Veterinary Anatomy, 4th Edition. Saunders Elsevier. 2010.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorDr. Shantel Julius, DVM Archives

April 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed